EaseHome is a revolutionary smart home chatbot that lets you control and monitor your home with ease. Using natural language processing and machine learning, EaseHome understands your voice commands and responds accordingly, making it easy to manage your home’s temperature, lighting, security, and more. With EaseHome, you can experience the future of smart home automation today.

Getting Started

EaseHome Tutorial

Welcome to EaseHome: A Smart Home Chatbot Tutoria

Imagine being able to converse with your home, effortlessly asking questions like “What’s the current temperature?” or “Are all doors locked?” and even controlling your home’s settings with simple voice commands like “Set the kitchen temperature to 19°C!” This futuristic vision, inspired by movies like “Minority Report,” is now within reach. In this tutorial, we’ll explore how to integrate a cutting-edge text recognition system into a smart home system using the Microsoft Bot Framework and Language Understanding Intelligent Service (LUIS).

The Dream of a Smart Home

The concept of a smart home has long fascinated us. With the advent of voice recognition and text-based interfaces, we can now bring this vision to life. Our goal is to create a seamless interaction between humans and their homes, enabling users to effortlessly control and monitor their living spaces. This tutorial will guide you through the design and implementation of EaseHome, a smart home chatbot that leverages the power of natural language processing and machine learning.

What to Expect

In this comprehensive tutorial, we’ll delve into the architecture and design of EaseHome, a Node.js powered bot that utilizes the Microsoft Bot Framework and LUIS. We’ll explore the skills and intentions behind our chatbot, configuration management, and the software and hardware mocks used to simulate a smart home system. Additionally, we’ll touch on the use of speech-to-text translation systems and provide a bonus section on integrating speech recognition with our chatbot.

To bring our smart home system to life, we’ll be using the following components:

- Microsoft Bot Framework: A set of tools for building conversational AI interfaces

- LUIS: A machine learning-based service for understanding natural language

- Node.js: A JavaScript runtime for building scalable server-side applications

- ASP.NET Web API: A framework for building web APIs using.NET

- Software Mock: A simulated smart home system for testing and development purposes

- Hardware Mock (Optional): A CC3200 and/or sensor tags-based hardware setup for a more realistic smart home experience

The Challenge of Building a Smart Home Platform

Creating a secure, reliable, and high-performance smart home platform is a daunting task, especially when considering the vast array of devices and use cases involved. Fortunately, commercial systems like RWE SmartHome have already tackled these challenges, providing a solid foundation for our project.

RWE SmartHome: A Comprehensive Solution

RWE SmartHome, a market leader in Germany, offers a secure and feature-rich platform that covers a wide range of devices and services. At the heart of this system lies the SmartHome Controller (SHC), a central unit that acts as a gateway for all integrated devices. The SHC connects devices, manages rules, and triggers actions when programmed conditions are met. Our bot service will interact with the SHC to read device states and send commands, using the same interface as standard UI clients.

RWE SmartHome Portfolio: A Broad Range of Devices

The RWE SmartHome portfolio includes a variety of core devices, such as radiator thermostats, window door sensors, pluggable switches, and motion detectors. These devices not only provide valuable information about their states (e.g., temperature, humidity, and door/window status) but also offer control capabilities, like adjusting room temperature and controlling lighting. With these devices, the possibilities for automation and monitoring seem endless.

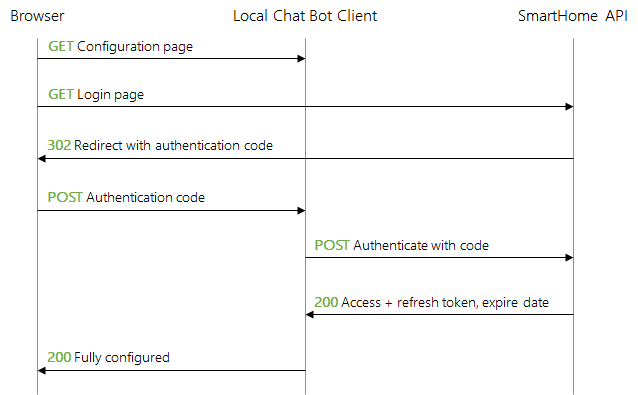

Communicating with the RWE SmartHome Gateway

To interact with the RWE SmartHome system, we need to communicate with the backend operated by RWE. This is achieved through a RESTful web API, which uses OAuth 2 for authentication. By registering a client, we can access the API and utilize its WebSocket channel to listen for events. For the purposes of this article, we’ll focus on passive actions, responding to requests without initiating active actions or notifications about state changes.

Designing the Smart Home Chatbot System

Now that we have a solid understanding of the RWE SmartHome solution, let’s dive into the architecture and implementation of our smart home bot system. We’ll start with a high-level overview and then drill down into the details of each component.

High-Level Architecture

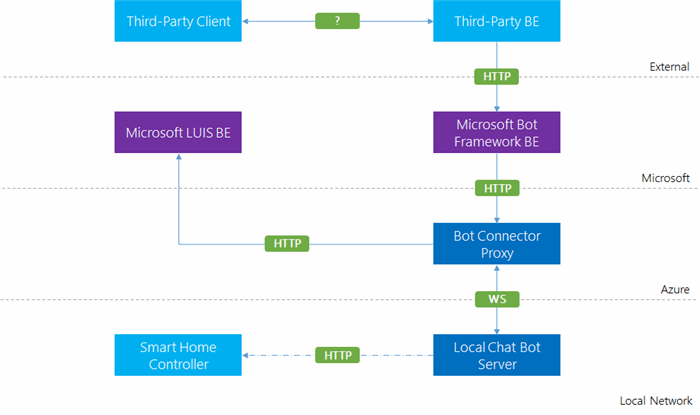

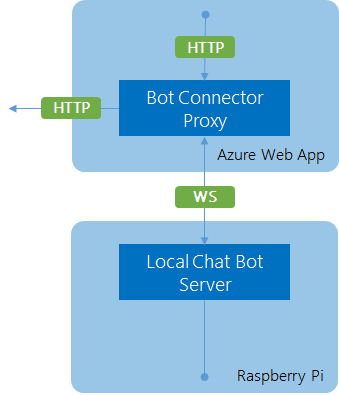

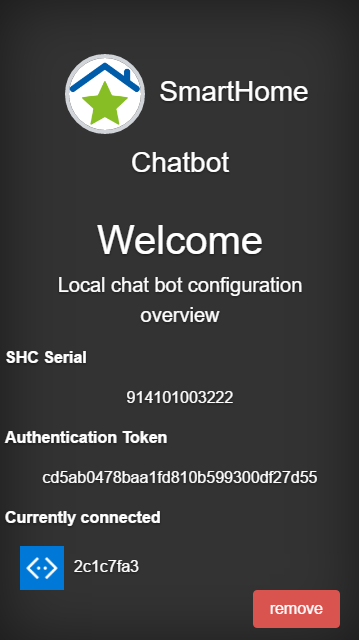

Our architecture consists of a local chatbot client running on a Raspberry Pi, connected to a central bot connector proxy hosted in Microsoft Azure via a WebSocket channel. The bot connector proxy provides a callback endpoint for the Microsoft Bot Connector and a channel registration endpoint for the local chatbot client. The local chatbot client is also connected to the RWE SmartHome system and hosts a small web server for configuration management.

The diagram below illustrates the high-level architecture of our solution, with purple components supplied by Microsoft, light blue components from third-party providers, and our custom components in darker blue.

We’ll focus on the two custom components: the proxy and the local chatbot client. The proxy offers an endpoint for Bot Framework callbacks and another endpoint for establishing WebSocket connections with local chatbot clients. It also uses HTTP to query LUIS. The local chatbot client connects to the proxy via WebSocket and uses an internal interface to gather information about the home.

Proxy Architecture

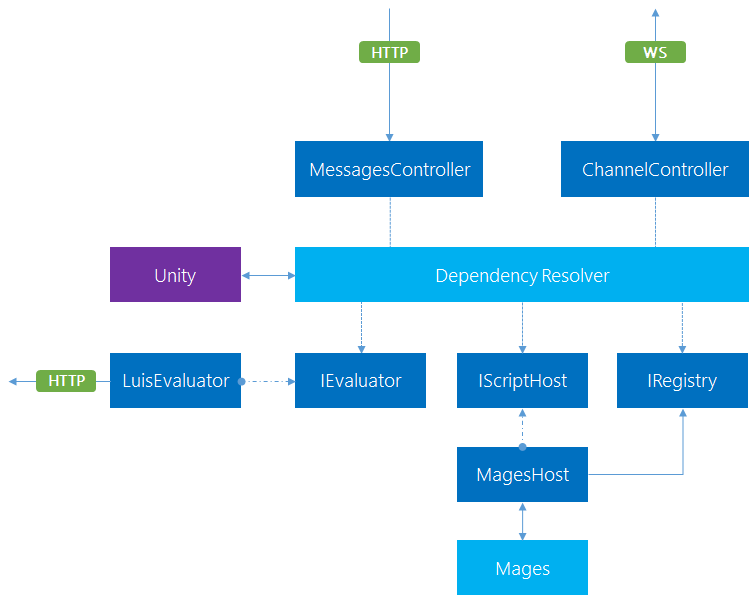

The proxy consists of two endpoints: the messages controller and the LUIS evaluation controller. The messages controller acts as a callback for the Microsoft Bot Connector, receiving messages and determining what to do with them. The LUIS evaluation controller evaluates the message using LUIS to determine the intent and entities.

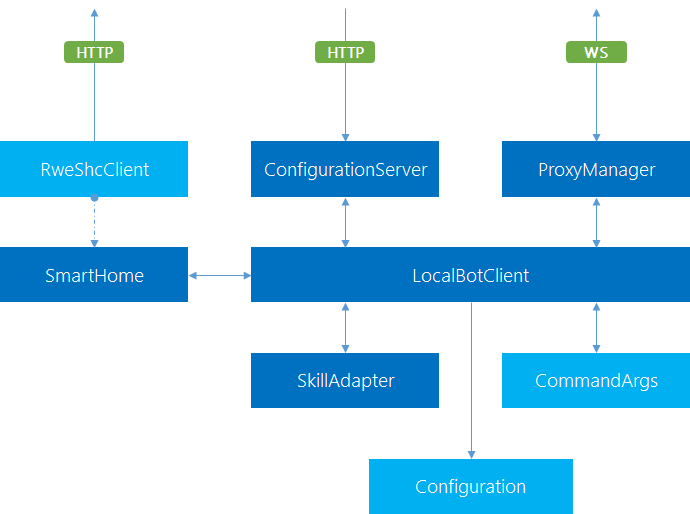

Local Chatbot Client Architecture

The local chatbot client centers around the bot client, which starts all components after reading the configuration. The components are wired together indirectly via events, allowing for loose coupling and easier testing. The most important flow is using the SmartHome component triggered by the ProxyManager in conjunction with the skill adapter, which maps intents to actions using the interface provided by the SmartHome component.

Additional Features

The local chatbot client also runs a web server for quick information and configuration management, and includes a command-line parser for flexibility in starting the application with different configurations or verbosity levels.

Microsoft Bot Framework and LUIS

In this section, we’ll delve deeper into the Microsoft Bot Framework and LUIS, which are key components of our smart home chatbot system.

Proxy Implementation

Our proxy is written in C# using the ASP.NET Web API framework and the Microsoft Bot Builder library. The /api/messages endpoint reacts to POST requests by calling the following action. The body of the request is serialized as an Activity instance.

public async Task<HttpResponseMessage> Post([FromBody]Activity activity)

{

if (activity.Type == ActivityTypes.Message)

{

/*... see below... */

}

else

{

SystemMessageHandlers.Handle(activity);

}

return Request.CreateResponse(HttpStatusCode.OK);

}

Handling System Messages

System messages are handled generically using the SystemMessageHandlers class.

public static class SystemMessageHandlers

{

private static readonly Dictionary<String, Func<Activity, Activity>> handlers = new Dictionary<String, Func<Activity, Activity>>

{

{ ActivityTypes.DeleteUserData, activity => null },

{ ActivityTypes.ConversationUpdate, activity => null },

{ ActivityTypes.ContactRelationUpdate, activity => null },

{ ActivityTypes.Typing, activity => null },

{ ActivityTypes.Ping, activity => null },

};

public static Activity Handle(Activity message)

{

var handler = default(Func<Activity, Activity>);

if (handlers.TryGetValue(message.Type, out handler))

{

return handler.Invoke(message);

}

return null;

}

}

Handling User Messages

For user messages, we need to evaluate the message using LUIS to determine the intent and entities.

var serviceUrl = new Uri(activity.ServiceUrl);

var connector = new ConnectorClient(serviceUrl);

var connection = _registry.GetFor(activity.ChannelId, activity.From.Id);

if (connection!= null)

{

await AskQuestionAsync(activity, serviceUrl, connection);

}

else

{

await TryRegisterAsync(activity, connector);

}

LUIS Evaluation

The AskQuestionAsync method uses an instance of IEvaluator to perform the evaluation of the message. The result is then sent to the connection that has been retrieved previously.

public async Task<String> EvaluateAsync(String input)

{

var query = Uri.EscapeDataString(input);

using (var client = new HttpClient())

{

var uri = $"https://api.projectoxford.ai/luis/v1/application?id={ApplicationId}&subscription-key={SubscriptionId}&q={query}";

var msg = await client.GetAsync(uri);

if (msg.IsSuccessStatusCode)

{

return await msg.Content.ReadAsStringAsync();

}

}

return null;

}

LUIS Project Definition

The LUIS project definition is a JSON file that contains all the information that represents our model. For the source code attached to this article, it is sufficient to illustrate the most simple model consisting of a single intent with an optional entity.

{

"luis_schema_version": "1.3.0",

"name": "EaseHome",

"desc": "Language understanding for a smart home platform.",

"culture": "en-us",

"intents": [

{

"name": "None"

},

{

"name": "get-temperature"

}

],

"entities": [

{

"name": "location"

}

],

"composites": [],

"bing_entities": [

"temperature",

"number",

"datetime"

],

"actions": [],

"model_features": [],

"regex_features": [],

"utterances": [

{

"text": "get the temperature.",

"intent": "get-temperature",

"entities": []

},

{

"text": "get the temperature in the bathroom.",

"intent": "get-temperature",

"entities": [

{

"entity": "location",

"startPos": 5,

"endPos": 5

}

]

},

...

]

}

The general tendency is to increase the accuracy by providing more utterances. Nevertheless, as we increase the number of intents, the utterances needed to keep the accuracy stable will increase exponentially.

Skills: Combining Intentions and Entities

The skill adapter is a crucial component that maps intents to JavaScript modules and calls the function exported from the module with the smart home adapter and the given entities. This allows us to handle queries from the proxy to the client in a flexible and modular way.

Skill Adapter Implementation

The skill adapter is a simple class that requires a smart home adapter to be created. The resolution of skills takes place in the resolve method, which looks for JavaScript files in the skills subfolder that match the name of the given intent.

const fs = require('fs');

const util = require('util');

const helpers = require('./helpers.js');

const EventEmitter = require('events').EventEmitter;

class Skills extends EventEmitter {

constructor(shc) {

super();

this.table = {};

this.shc = shc;

}

resolve(id, intent, entities) {

const fn = __dirname + '/skills/' + intent + '.js';

if (!intent ||!fs.existsSync(fn)) {

return this.emit('failure', id);

}

const stats = fs.statSync(fn);

const changed = new Date(util.inspect(stats.mtime));

if (!this.table[intent] || changed > this.table[intent].changed) {

this.table[intent] = {

changed: changed,

execute: helpers.getModule(fn)

};

}

this.table[intent].execute(this.shc, entities).then((message) => {

this.emit('success', id, message);

}).catch((err) => {

return this.emit('failure', id);

});

};

};

module.exports = Skills;

Example Skill: Get Temperature

Here is an example of a skill that retrieves the temperature from the smart home adapter. The get-temperature skill uses the smart home adapter to retrieve all temperature states asynchronously. Once the values are known, it filters the result set based on the entities provided.

const Promise = require('promise');

module.exports = function(shc, entities) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

shc.getAllStates('Temperature').then(function(temperatures) {

const sentences = [];

if (entities.length > 0) {

const original = temperatures;

temperatures = [];

entities.forEach(function(entity) {

if (entity.type === 'location') {

const location = entity.name.toUpperCase();

temperatures = temperatures.concat(original.filter(function(temperature) {

return temperature.location && temperature.location.toUpperCase() === location;

}));

}

});

} else {

const sum = temperatures.reduce((c, nxt) => c + nxt.state.value, 0);

sentences.push('The average temperature is'+ (sum / temperatures.length) + '°C.');

}

const values = temperatures.map(function(temperature) {

return [temperature.state.value, '°C in ', temperature.location,'(', temperature.device.name, ')'].join('');

});

if (values.length > 0) {

const message = values.join(', ');

sentences.push('The temperature is'+ message + '.');

}

if (sentences.length === 0) {

sentences.push('No temperature sensor readings found.');

}

return resolve(sentences.join(' '));

}).catch(function(err) {

return reject(err);

});

});

};

The best thing about skills is that they can be extended or improved during runtime, allowing the system to evolve as more intents are modeled. This is great for prototyping or for an update process that is to be defined later.

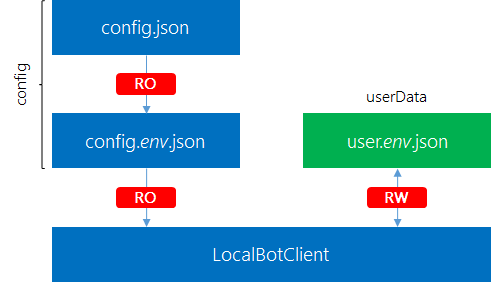

Configuration Management

To simplify development, a configuration management system has been established that is both simple and flexible. The system aggregates all important settings in a single JSON file and allows for specialization of these settings in another file. The primary file is always loaded, while the specialized file is only loaded upon request (i.e., if a file with the given name exists). Settings in the specialized file override or extend the settings in the primary file.

Environment Specialization

The specialization is called an environment. The primary settings file is the global file, while the specialized file is the environment (or local) file. The environment file follows the naming convention of having a file name without extension that ends with .environmentname, where environmentname represents the chosen environment name. For development, two specializations have been used: debug and release (reasonable and familiar choices).

Global and Environment Files

The global file contains generic settings, while the environment file contains specialized settings that override or extend the global settings. For example, the global file might contain:

{

"adapter": {

"host": "smarthomebot.azurewebsites.net"

},

"webserver": {

"port": 3000,

"assets": "assets",

"views": "views"

},

"smarthome": { }

}

While the environment file for the debug environment might contain:

{

"adapter": {

"host": "localhost:3979"

}

}

User Configuration

A local chat bot client is mapped to a single user by definition. The user may have different accounts registered in different channels (e.g., Skype, Slack,…). The userData file is bound to an environment, as different environments may use different connection URLs and smart home credentials. Therefore, it makes sense to specialize the user configuration with the given environment.

Hierarchical Configuration vs. User Data

The configuration is read-only and never modified by the application, while the user data is populated exclusively by the application. The user data file is used to store persistent information about the user, which is used to continue with the previous state on application restart. This file also stores the refresh token (see OAuth 2 flow) required to get an access token for the smart home system.

Security Considerations

Storing the refresh token unencrypted is a security risk. For a client that will be deployed, the refresh token should never be stored in an unencrypted fashion.

Web Server Configuration

The web server is configured using a wrapper class that provides loose coupling between the rest of the application and the web server. The routes are part of this abstraction layer. The WebServer class is used to render the JADE view engine.

const express = require('express');

const bodyParser = require('body-parser');

const EventEmitter = require('events').EventEmitter;

class WebServer extends EventEmitter {

constructor(config) {

super();

const app = express();

app.use(express.static(__dirname + '/../' + config.assets));

app.use(bodyParser.urlencoded({ extended: true }));

app.set('views', __dirname + '/../' + config.views);

app.set('view engine', 'jade');

app.get('/', (req, res) => {

const model = {};

this.emit('index', model);

res.render('index', model);

});

app.post('/revoke', (req, res) => {

const data = req.body;

const model = { data: data };

this.emit('revoke', model);

res.redirect('/');

});

app.post('/setup', (req, res) => {

const data = req.body;

const model = { data: data };

this.emit('setup', model);

res.render('setup', model);

});

app.listen(config.port, () => {

console.log('Webserver started at port %s!', config.port);

});

}

};

module.exports = WebServer;

This concludes the configuration management in our chat bot.

Getting Started with the Code

The code we’ve developed so far is designed to be usable from the start, but we also recognize that you may need to switch to a different smart home provider in the future. To accommodate this, our solution doesn’t come bundled with a specific provider, such as RWE SmartHome. Instead, we’ve included a generic software provider and two hardware providers that you can use.

The choice of provider is entirely up to you. We’ve designed the system to be highly configurable, making it easy to switch between providers or even create your own custom provider. This flexibility also means that you can integrate your custom provider with an existing home automation system or any other tool of your choice.

To get started, you’ll need to configure the system by supplying the required parameters.

Bot Connector Proxy Setup

The bot connector proxy is an ASP.NET Web API project. To deploy or test the solution, you’ll need to update the web.config file with the required parameters. The file should look like this:

<configuration>

<appSettings>

<add key="BotId" value="" />

<add key="MicrosoftAppId" value="" />

<add key="MicrosoftAppPassword" value="" />

<add key="LuisApplicationId" value="" />

<add key="LuisSubscriptionId" value="" />

</appSettings>

<!--... -->

</configuration>

Fill in the required fields for deployment, or provide at least the LuisApplicationId and LuisSubscriptionId values for testing.

The Software Mock

Any smart home adapter must implement the SmartHomeAdapter interface, which includes methods for refreshing, logging in, and retrieving device states. Our software mock should be simple, flexible, and suitable for unit testing and integration with other hardware.

Here’s an example of a simple software mock:

class SmartHomeClient {

constructor(config) {

this.loggedIn = false;

}

getAllLocations() {

return Promise.resolve({ /*... */ });

}

getAllDevices() {

return Promise.resolve({ /*... */ });

}

getAllCapabilities() {

return Promise.resolve({ /*... */ });

}

getAllCapabilityStates() {

return Promise.resolve({ /*... */ });

}

authorizeWithRefresh(refreshToken) {

this.loggedIn = true;

return Promise.resolve({ /*... */ });

}

authorize(code) {

return this.authorizeWithRefresh(code);

}

}

module.exports = SmartHomeClient;

To make the mock more useful, we can add configuration options to transport predefined sets of devices, locations, and capabilities. We can also use a module to load data from local files, making it easier to integrate with hardware.

Building a Resolver

A key function in our software mock is the buildResolver function, which creates a resolver from a given function or entities. This function is used in the constructor to resolve devices, locations, and capabilities.

function buildResolver(resolver, entities) {

if (typeof resolver ==='string') {

resolver = eval(resolver);

} else if (resolver && typeof resolver!== 'function') {

entities = resolver;

resolver = undefined;

}

if (!resolver) {

if (entities) {

resolver = () => entities;

} else {

resolver = () => [];

}

}

return resolver;

}

This function is used to create resolvers for devices, locations, and capabilities, making it easy to customize the behavior of the software mock.

Helper Functions

To make it easier to work with the software mock, we’ve also included some helpful functions for reading files and parsing JSON data. These functions can be used to quickly load data from local files and integrate with hardware.

function readLinesFromFile(fn) {

const data = fs.readFileSync(fn, 'utf8');

return data.trim().split('\n');

}

function readLastLineFromFile(fn) {

const lines = readLinesFromFile(fn);

return lines.slice(-1)[0];

}

function readFileAsJson(fn) {

const data = fs.readFileSync(fn, 'utf8');

return JSON.parse(data);

}

With these helper functions and the software mock in place, you’re ready to start building your smart home solution with EaseHome.

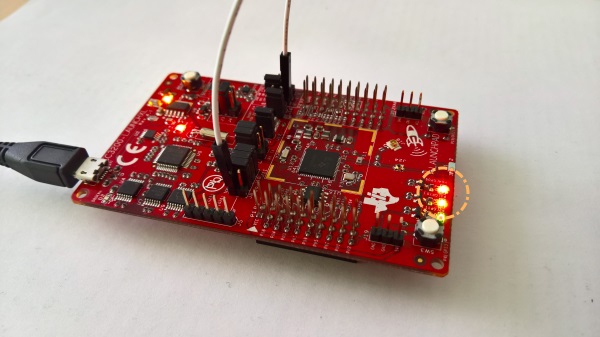

Using a Single CC3200 Instance

While the software mock is a great way to experiment with the smart home chatbot solution, eventually, we’ll want to connect it to real sensors. However, we may not want to invest in a comprehensive smart home system like RWE SmartHome, especially if it’s not available in our region or doesn’t provide an API. In such cases, a lightweight solution like the CC3200 microcontroller unit (MCU) can be a suitable substitute.

The CC3200 is a powerful MCU that comes with a development board called the CC3200-LaunchXL. This board is equipped with extension possibilities and integrated sensors, including a temperature sensor, making it an ideal choice for our project.

In this section, we’ll guide you through the necessary steps to set up a CC3200 development board and program it to read sensor data and periodically send it to a local server, where the chatbot is running.

Requirements

To use a CC3200 for obtaining sensor data, you’ll need:

- The TI CC3200-LaunchXL board

- A USB micro cable

- The Energia IDE installed

- Internet access via WiFi for the CC3200

- A code editor of your choice (e.g., Energia, Sublime Text, Emacs, or vim)

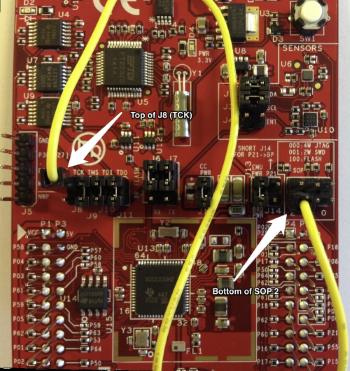

Connecting the LaunchPad

To get started with the LaunchPad, simply press CTRL + M in Energia. This will compile the binaries, upload the code, open the serial monitor, and run the application. However, the LaunchPad’s design makes it less than ideal for a quick build-test-debug loop. You’ll need to set different jumpers to switch between run-mode and program-mode.

Here’s a neat workaround using the J8 (TOP) connector and the SOP2 (BOTTOM) connector:

By following these steps, you can simplify the process:

- Remove both jumpers J8 and SOP2 (if installed).

- Connect one side of the jumper wire to the top of J8 and the other side to the bottom of SOP2.

- Run the code from Energia via CTRL + M. You should see the serial monitor pop up (make sure to configure the correct baud rate!) and the LEDs start blinking.

Now that we have our setup working, let’s take it to the next level. We can either use one of the buttons (PUSH1 or PUSH2) or leverage an integrated sensor. For the buttons, we’d use digitalRead to get the state (HIGH or LOW) and constantly monitor the current state via polling. But let’s skip the buttons and dive straight into using sensor input.

Making HTTP Requests

We’ve made significant progress so far, from a simple “Hello World” to gathering sensor information and triggering outputs based on that data. Now, we’re ready to take the critical step of adding wireless connectivity to the world wide web, enabling IoT applications.

To demonstrate this, we’ll use httpbin.org to make an HTTP request to its API, retrieve a single integer, and display the result using a blinking LED. We’ll also insert a five-second pause (LED off) after each HTTP call.

ESTABLISHING A NETWORK CONNECTION

Before we can make an HTTP call, we need to establish a network connection. Fortunately, the CC3200 LaunchPad comes with a WiFi chip on-board. We’ll create a new file, wifi.cpp, to handle the WiFi connection.

The header file is simple, declaring a single function:

#pragma once

void connectWifi(char* ssid, char* password);

The source file contains print statements for debugging and uses the WiFi library that comes with Energia:

#include "wifi.h"

#include <Energia.h>

#include <WiFi.h>

void connectWifi(char* ssid, char* password) {

Serial.print("Connecting to WIFI network ");

Serial.print(ssid);

WiFi.begin(ssid, password);

while (WiFi.status()!= WL_CONNECTED) {

Serial.print(".");

delay(300);

}

Serial.println(" connected!");

Serial.print("Waiting for an IP address ");

while (WiFi.localIP() == INADDR_NONE) {

Serial.print(".");

delay(300);

}

Serial.println(" received!");

}

The code establishes a WiFi connection, waits for the connection to be established, and then waits for the router to assign an IP address.

MAKING AN HTTP REQUEST

Now that we have a WiFi connection, we can make an HTTP request. We’ll create a new function, httpGetRequest, to handle this:

bool httpGetRequest(char* hostname, char* path);

The function takes a hostname (e.g., httpbin.org) and a path (e.g., /bytes/4) as input. The source code for the function is:

#include <Energia.h>

#include <WiFi.h>

bool httpGetRequest(char* host, char* path) {

String hostname = String(host);

String head_post = "GET " + String(path) + " HTTP/1.1";

String head_host = "Host: " + hostname;

String request = head_post + "\n" +

head_host + "\n\n";

char receive_msg_buffer[1024];

uint32_t host_ip;

bool success = false;

SlTimeval_t timeout {.tv_sec = 45,.tv_usec = 0 };

if (sl_NetAppDnsGetHostByName((signed char*)hostname.c_str(), hostname.length(), &host_ip, SL_AF_INET)) {

return false;

}

SlSockAddrIn_t socket_address {

.sin_family = SL_AF_INET,.sin_port = sl_Htons(80),.sin_addr = {.s_addr = sl_Htonl(host_ip) }

};

uint16_t socket_handle = sl_Socket(SL_AF_INET, SL_SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_TCP);

if (sl_SetSockOpt(socket_handle, SL_SOL_SOCKET, SL_SO_RCVTIMEO, (const void*)&timeout, sizeof(timeout)) >= 0 &&

sl_Connect(socket_handle, (SlSockAddr_t*)&socket_address, sizeof(SlSockAddrIn_t)) >= 0 &&

sl_Send(socket_handle, request.c_str(), request.length(), 0) >= 0 &&

sl_Recv(socket_handle, receive_msg_buffer, sizeof(receive_msg_buffer), 0) >= 0) {

Serial.println(receive_msg_buffer);

success = true;

}

sl_Close(socket_handle);

return success;

}

The function defines the request message to send, retrieves the IP address of the host, sets up the connection socket, and sends the request. The response is received as a single string, which needs to be parsed to extract the desired information.

When we run this code, we should see a response similar to:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Server: nginx

Date: Sat, 18 Jun 2016 07:24:31 GMT

Content-Type: application/octet-stream

Content-Length: 4

Connection: keep-alive

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *

Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: true

L8=r

The last characters are the string representation of the 4 random bytes we’re interested in. Note that a random binary byte may not correspond to a printable ASCII symbol.

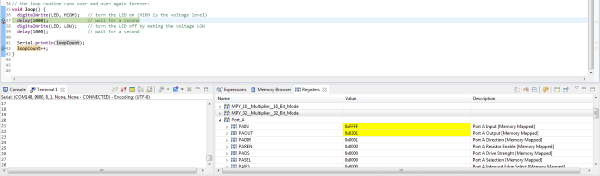

Playing with the LaunchPad

Debugging software on embedded systems like the CC3200 LaunchPad can be a challenging task. Unlike traditional programming, we don’t have access to the same tooling and techniques we’re familiar with. However, there are still ways to gain insights into what’s happening on the device.

One useful utility is the Serial class, which allows us to print messages to the serial interface and gain some understanding of the system’s behavior. The CC3200 LaunchPad also features a JTAG (4-wire) and SWD (2-wire) interface for development and debugging, but we won’t be exploring those in this tutorial.

Instead, we’ll focus on using the serial interface provided by the FTDI connector via USB. We’ve already seen how writing messages to the serial interface can be helpful, but an even more powerful approach is to use the Code Composer Studio (CCS) from Texas Instruments. CCS allows us to set breakpoints, which is a much more efficient and effective way to debug our code.

To get started with CCS, we’ll need to download and install it, then set it up to connect to the correct COM port with the configured bandwidth. It’s also important to configure CCS to point to the Energia installation path, otherwise, it may not be able to find the required libraries and files. Once we’ve done that, we can open Energia projects directly from CCS.

One of the cool features of CCS is its ability to view the currently used registers and memory directly. This can be a huge help in tracking down errors in our code.

With CCS, we can accelerate our search for errors and get back to solving our original problem: making a secure HTTP request from the CC3200.

Digging Into the Accelerometer

The CC3200 LaunchPad comes equipped with several sensors, including a temperature sensor (tmp006) at address 0x41 and an accelerometer (bma222) at address 0x18. In this example, we’ll focus on using the accelerometer, which is easier to work with for demo purposes.

IMPORTANT NOTE

Due to an overlap in the address register, we can’t use the yellow and green LEDs together with the accelerometer. Therefore, we’ll only use the red LED from now on.

To read the accelerometer sensor, we’ll include the Wire.h header and create a new file called accelerometer.cpp with a corresponding header file accelerometer.h. Our initial code looks like this:

#include <Wire.h>

#include "accelerometer.h"

void setup() {

Serial.begin(9600);

Serial.println("Entering setup!");

Wire.begin();

pinMode(RED_LED, OUTPUT);

}

void loop() {

Serial.println("Next loop iteration!");

AccData acc = readAccelerometer();

Serial.print(acc.x);

Serial.print(", ");

Serial.print(acc.y);

Serial.print(", ");

Serial.println(acc.z);

digitalWrite(RED_LED, HIGH);

delay(1000);

}

The readAccelerometer function is declared in our new header file. In the setup function, we need to initialize the Wire library. In each iteration, we read the accelerometer and print the values to the screen.

The AccData structure is defined in our header file as follows:

#pragma once

#include <stdint.h>

struct AccData {

int8_t x;

int8_t y;

int8_t z;

};

AccData readAccelerometer();

The source file is more interesting, where we define the readAccelerometer function:

#include "accelerometer.h"

//...

int8_t readSingleAxis(uint8_t axis);

AccData readAccelerometer() {

AccData data;

data.x = readSingleAxis(0x03);

data.y = readSingleAxis(0x05);

data.z = readSingleAxis(0x07);

return data;

}

We read the registers for each component of the three-dimensional acceleration vector and return the full result.

The readSingleAxis function is defined as follows:

#include <Energia.h>

#include <Wire.h>

void initializeI2C(uint8_t base_address, uint8_t register_address) {

Wire.beginTransmission(base_address);

Wire.write(register_address);

Wire.endTransmission();

}

uint8_t readI2C(uint8_t base_address, uint8_t register_address) {

initializeI2C(base_address, register_address);

Wire.requestFrom(base_address, 1);

while (Wire.available() < 1);

return Wire.read();

}

int8_t readSingleAxis(uint8_t axis) {

return readI2C(0x18, axis);

}

Each read operation starts an I2C connection to the device at the given address. We use the Wire library to abstract away the low-level I2C communication protocol.

Now that we have the accelerometer data, we can modify the code in the loop function to show the red light when the board is “falling”. From our elementary physics course, we know that a free-falling body is essentially force-free, meaning the acceleration in the z-direction will be zero (compared to 1g for a body standing on the earth’s surface). We assume the z-axis of the accelerometer is pointing upwards.

We measure a value of approximately 65 in the z-direction by default, so we can normalize to this value. We’ll show a red light for values below 0.4g, i.e., when the value drops below 26. Our modified code looks like this:

#include <Wire.h>

#include "accelerometer.h"

void setup() {

Serial.begin(9600);

Wire.begin();

pinMode(RED_LED, OUTPUT);

}

void loop() {

AccData acc = readAccelerometer();

Serial.println(acc.z);

if (acc.z > 26) {

digitalWrite(RED_LED, LOW);

} else {

digitalWrite(RED_LED, HIGH);

}

}

If we want the warning to stay active for at least 1 second, we can modify the code to look like this:

if (acc.z > 26) {

digitalWrite(RED_LED, LOW);

} else {

digitalWrite(RED_LED, HIGH);

delay(1000);

}

The red LED will light up for at least 1 second once triggered.

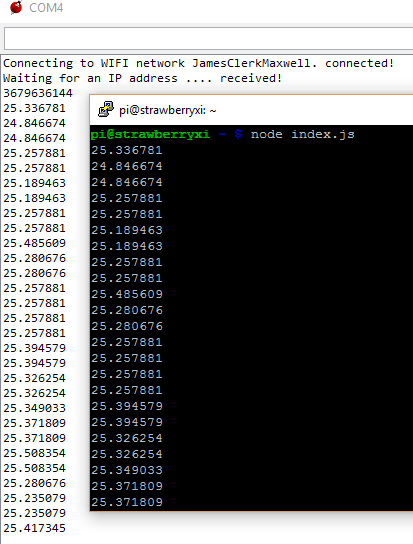

Reading and Sending the Temperature

To receive and store the temperature data, we can set up a simple Node.js express server (e.g., listening on port 3000). The server code can be as follows:

const express = require('express');

const app = express();

app.use((req, res, next) => {

req.rawBody = '';

req.setEncoding('utf8');

req.on('data', (chunk) => {

req.rawBody += chunk;

});

req.on('end', () => {

next();

});

});

app.post('/temperature', (req, res) => {

console.log(req.rawBody);

// Process the raw value as needed

res.send('');

});

app.listen(3000);

With our previously established helpers in place, we can write concise and functional code for the CC3200.

The following code connects to the local WiFi, initializes the temperature sensor, and continuously reads the sensor data with a 2-second interval (for illustration purposes).

Adafruit_TMP006 tmp006(0x41);

void setup() {

Serial.begin(9600);

connectWifi(WLAN_PUB_SSID, WLAN_KEY_CODE);

tmp006.begin();

tmp006.wake();

setCurrentTime();

}

void loop() {

char receive_msg_buffer[1024];

char send_msg_buffer[128];

while (true) {

delay(2000);

float value = tmp006.readObjTempC();

sprintf(send_msg_buffer, "%lf", value);

Serial.println(send_msg_buffer);

httpPostRequest(TMP_SNSR_HOST, TMP_SNSR_PORT, TMP_SNSR_PATH, send_msg_buffer, receive_msg_buffer);

}

}

By following these steps, we can successfully read and transport the temperature data. Let’s verify this using the debugger.

Expanding Sensor Capabilities with Multiple Tags

When a single CC3200 is not sufficient, we can leverage multiple temperature sensors connected via Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE). This approach can be more straightforward than using the CC3200, which requires low-level hardware details to read sensor data and perform HTTP requests on a minimal operating system.

SensorTag and Raspberry Pi Integration

We can utilize a TI SensorTag with a Raspberry Pi 3 to retrieve temperature readings via BLE.

PREREQUISITES

To fully integrate this approach into our setup, we need:

- An active Bluetooth connection on the Raspberry Pi

- At least one TI SensorTag

- A text editor installed on the Raspberry Pi 3, such as nano, ed, or vim

- The Raspbian Jessie image on the Raspberry Pi 3, which comes with Bluetooth drivers (otherwise, run sudo apt-get install pi-bluetooth)

CONFIGURING THE HARDWARE ENVIRONMENT

We begin by setting up the hardware environment. The software should be pre-configured, especially if we choose to use one of the available images.

EXPLORING BLUETOOTH FROM THE COMMAND LINE

We connect to the Raspberry Pi using our favorite SSH client (e.g., Putty on Windows). In the shell, we can explore the TI SensorTag using the following instructions:

- Run the standard Bluetooth program by typing bluetoothctl.

- Enable Bluetooth if it’s not already on by typing power on. Similarly, disable Bluetooth with power off.

- Use the devices command to list paired devices.

- Enter device discovery mode with scan on. After some time, the sensor tag should appear (e.g., with MAC address 34:B1:F7:D4:F2:CF).

- Enter pair 34:B1:F7:D4:F2:CF to create the pairing between the Pi and the sensor tag.

- Stop discovering devices with scan off.

- Exit the program by typing quit.

This way, we’ve discovered and paired our device. Now we can use gatttool to interact with the sensor tag.

INTERACTING WITH THE SENSOR TAG USING GATTTOOL

- Run the program by typing gatttool -b 34:B1:F7:D4:F2:CF –interactive. We enter an interactive session.

- The first command we issue is connect. We should see a “Connection successful” message.

- Now we can attempt to read from the sensor tag: char-read-hnd 0x25 uses the handle 0x25 to read data from the thermometer. We should see some zeros.

- To read some values, we need to enable the thermometer. We issue char-write-cmd 0x29 01 to turn the thermometer sensor at 0x29 on.

- Issuing the command char-read-hnd 0x25 again should now yield a non-zero value.

- Exit the program by typing quit.

Sensor Handles

The TI SensorTag comes equipped with a variety of sensors, including:

- Contactless IR temperature sensor (Texas Instruments TMP006)

- Humidity sensor (Sensirion SHT21)

- Gyroscope (Invensense IMU-3000)

- Accelerometer (Kionix KXTJ9)

- Magnetometer (Freescale MAG3110)

- Barometric pressure sensor (Epcos T5400)

- On-chip temperature sensor (Built into the CC2541)

- Battery/voltage sensor (Built into the CC2541)

Each sensor has its own unique handle, which is used to interact with it. The following table provides a brief overview of some of the sensors and their corresponding handles:

| Sensor | Read Handle | Length | Configure Handle | Data Handle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR Temperature | 0x25 | 4 bytes | 0x29 | 0x26 |

| Accelerometer | 0x2d | 3 bytes | 0x31 | 0x2e |

| Humidity | 0x38 | 4 bytes | 0x3c | 0x39 |

| Magnetometer | 0x40 | 6 bytes | 0x44 | 0x41 |

| Barometric Pressure | 0x4b | 4 bytes | 0x4f | 0x4c |

| Gyroscope | 0x57 | 6 bytes | 0x5b | 0x58 |

The barometric pressure sensor requires an extra calibration step, which must be performed before taking the first measurement. This involves issuing the command char-write-cmd 0x4f 02 to perform the calibration, and then reading the raw value using char-read-hnd 0x52.

The following image shows a detailed map of the sensor components on the SensorTag board.

SensorTag Hardware

With this information, we can now write a simple bash script to query the sensors at regular intervals and write the results to a text file. This script can be used to pair devices, read sensor values, and perform other tasks.

For example, the following script pairs all devices listed in a file called devices.

#!/bin/bash

bluetoothctl <<< "power on"

sleep 1s

bluetoothctl <<< "scan on"

sleep 5s

while IFS='' read -r line || [[ -n "$line" ]]; do

bluetoothctl <<< "pair ${line}"

done < devices

sleep 4s

while IFS='' read -r line || [[ -n "$line" ]]; do

bluetoothctl <<< "disconnect ${line}"

done < devices

We can use a similar script to read temperature sensor values from these devices.

#!/bin/bash

while IFS='' read -r line || [[ -n "$line" ]]; do

gatttool -b ${line} --char-write -a 0x29 -n 01

gatttool -b ${line} --char-read -a 0x25

done < devices

From here, it’s easy to continue polling the device at regular intervals (e.g., every five minutes) to gather information about the temperature.

Unlocking the Power of Speech-to-Text

Once we have established a robust text layer, the possibilities for innovation are endless. One of the most exciting opportunities is to integrate a speech-to-text layer on top of our design. While some clients, such as Skype on mobile platforms, offer this functionality for free, we may want to create a custom application that provides voice recognition as an input option.

Integrating with Direct Line

To integrate a speech-to-text client with our chatbot system, we can utilize a direct line. By leveraging the Microsoft.Bot.Connector.DirectLine package from NuGet, we can create a custom channel that interacts with our chatbot API.

The following code demonstrates how to get started with creating our own chat client:

sealed class MessageChannel : IDisposable

{

private static readonly string BingSecret = ConfigurationManager.AppSettings["BingSecret"];

private static readonly string EndPoint = ConfigurationManager.AppSettings["SmartBotEndpoint"];

private static readonly Uri DirectLine = new Uri("https://directline.botframework.com");

private readonly Conversation _conversation;

private readonly DirectLineClient _client;

public event EventHandler<MessageEvent> Received;

public MessageChannel()

{

var credentials = new DirectLineClientCredentials(BingSecret, EndPoint);

_client = new DirectLineClient(DirectLine, credentials);

_conversation = _client.Conversations.NewConversation();

}

public Task SendAsync(string content)

{

var message = new Message(text: content);

return _client.Conversations.PostMessageAsync(_conversation.ConversationId, message);

}

public async Task ReceiveAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var watermark = default(string);

while (!cancellationToken.IsCancellationRequested)

{

var messages = await _client.Conversations.GetMessagesAsync(_conversation.ConversationId, watermark, cancellationToken);

foreach (var message in messages.Messages)

{

Received?.Invoke(this, new MessageEvent(message.Text, message.Created, message.FromProperty));

}

watermark = messages.Watermark;

}

}

public void Dispose()

{

_client.Dispose();

}

}

The SendAsync method posts a single message to the conversation, while the ReceiveAsync method retrieves messages from the conversation, including those sent by our chatbot. By using a watermark, we can retrieve only the new messages since the last retrieval, effectively implementing a long polling mechanism. The received messages are then delivered as events.

Bing Speech-To-Text Integration

One of the simplest ways to incorporate speech recognition into a C# application is by utilizing the Bing Speech-To-Text API. We can leverage the Microsoft.ProjectOxford.SpeechRecognition-x64 package, available on NuGet, to create a VoiceChannel class that enables microphone input.

The beauty of this library lies in its simplicity. All we need to do is create a new client using the SpeechRecognitionServiceFactory factory. In our case, we want to utilize the Bing Speech-To-Text service and integrate it with our defined model, which is currently residing in LUIS. Therefore, we use the CreateMicrophoneClientWithIntent method. Besides the obvious Bing subscription, we also need to supply our LUIS application and subscription ID. The rest is handled internally.

The library even takes care of finding and controlling the microphone, including recording and other tasks. A few events make the library smooth and easy to work with.

The following code illustrates the basic usage:

sealed class VoiceChannel : IDisposable

{

private static string SpeechLocale = ConfigurationManager.AppSettings["SpeechLocale"];

private static string LuisApplicationId = ConfigurationManager.AppSettings["LuisApplicationId"];

private static string LuisSubscriptionId = ConfigurationManager.AppSettings["LuisSubscriptionId"];

private static string BingPrimaryKey = ConfigurationManager.AppSettings["BingPrimaryKey"];

private static string BingSecondaryKey = ConfigurationManager.AppSettings["BingSecondaryKey"];

private readonly MicrophoneRecognitionClientWithIntent _mic;

private bool _recording;

public event EventHandler<IntentEvent> ReceivedIntent

{

add { _mic.OnIntent += (sender, ev) => value.Invoke(sender, new IntentEvent(ev.Payload)); }

remove { _mic.OnIntent -= (sender, ev) => value.Invoke(sender, new IntentEvent(ev.Payload)); }

}

public VoiceChannel()

{

_recording = false;

_mic = SpeechRecognitionServiceFactory.CreateMicrophoneClientWithIntent(

SpeechLocale,

BingPrimaryKey,

BingSecondaryKey,

LuisApplicationId,

LuisSubscriptionId);

_mic.OnResponseReceived += OnResponseReceived;

_mic.OnMicrophoneStatus += OnMicrophoneStatus;

}

public bool IsRecording

{

get { return _recording; }

}

public void ToggleRecording()

{

if (_recording)

{

_mic.EndMicAndRecognition();

}

else

{

_mic.StartMicAndRecognition();

}

}

private void OnMicrophoneStatus(object sender, MicrophoneEventArgs e)

{

_recording = e.Recording;

}

private void OnResponseReceived(object sender, SpeechResponseEventArgs e)

{

foreach (var phrase in e.PhraseResponse?.Results?? Enumerable.Empty<RecognizedPhrase>())

{

Debug.WriteLine(phrase.DisplayText);

}

}

public void Dispose()

{

_mic.Dispose();

}

}

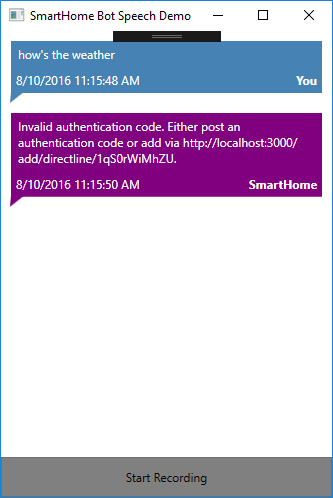

With speech recognition available, we can easily wire everything together. In the end, the UI can be as simple as having a button to start and end the speech recognition, and a message dialog to display all the performed questions and answers.

Additionally, we may also want to integrate speech output, which can be done using the System.Speech library (deployed with Windows 8+ and.NET 4.5).

Text-to-Speech Synthesis

Utilizing a speech synthesizer is a cost-effective and reliable way to provide basic audio output, which can be particularly useful for enhancing accessibility. While accessibility is not the primary focus of our scenario, we can leverage this technology to create a cool and engaging experience.

The following code implements a simple text-to-speech synthesizer. Note that the class is a minimal wrapper, and the SpeakAsync method does not return a Task. To determine when the message has finished playing, we need to check the IsCompleted property of the returned prompt. For brevity, we have kept the implementation simple and minimal, omitting additional logic such as message queuing.

sealed class SpeechChannel : IDisposable

{

private readonly SpeechSynthesizer _synthesizer;

public SpeechChannel()

{

_synthesizer = new SpeechSynthesizer();

}

public void Dispose()

{

_synthesizer.Dispose();

}

public void Say(string message)

{

_synthesizer.SpeakAsync(message);

}

}

The screenshot below shows the final result, a lightweight WPF application that consists of an item control and a button. The messages are received continuously, providing a seamless user experience.

Configuring the Speech Client

To utilize the speech client, we need to provide some essential configuration settings. These settings are stored in the app.config file of the provided source code.

The following XML snippet highlights the fields that require input:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<configuration>

<appSettings>

<add key="LuisApplicationId" value="/* Enter Your LUIS Application ID here */" />

<add key="LuisSubscriptionId" value="/* Enter Your LUIS Subscription ID here */" />

<add key="SpeechLocale" value="en-US" />

<add key="BingPrimaryKey" value="/* Enter Your Bing Speech-To-Text Primary Key ID here */" />

<add key="BingSecondaryKey" value="/* Enter Your Bing Speech-To-Text Secondary Key ID here */" />

<add key="DirectLineSecret" value="/* Enter Your Direct Line Secret here */" />

<add key="SmartBotEndpoint" value="/* Enter Your Chat Bot API Endpoint here */" />

</appSettings>

<!--... -->

</configuration>

In addition to the LUIS subscription, which provides the Bing Speech-To-Text service with more information and a model for resolution, we also require a Bing Speech-To-Text subscription, currently available as a preview. We can obtain the primary and secondary key from the Bing Speech-To-Text webpage. Furthermore, we need to provide the secret for the direct line connection, which ensures that our client is authorized to communicate with our bot adapter.

Expanding the System’s Capabilities

The system’s flexibility allows for seamless integration with other home automation facilities, making it a versatile tool for managing various aspects of one’s life. I have personally extended the system to monitor server infrastructure and multimedia offerings, freeing myself from the need for platform-specific apps. With the chatbot at my fingertips, I can simply send messages like “pause the current movie” or “increase the volume by 5%” to control my devices.

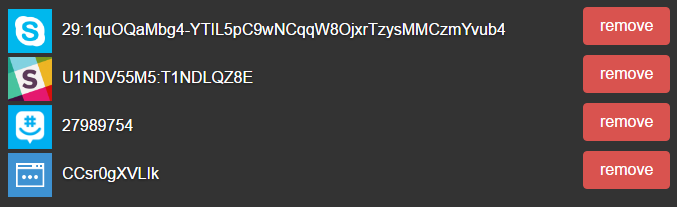

Adding new intents to the system is a straightforward process, making it easy to expand its capabilities. Currently, I have three channels permanently connected to my bot, with the web chat serving as a fourth channel, as shown in the screenshot below.

The system allows for connections via multiple channels, including Skype, Slack, and GroupMe, providing users with flexibility and convenience. While each channel is distinct, we could potentially store conversation-specific logic on the local chatbot client, enabling us to break conversation boundaries and leverage information from one channel to answer questions in another. However, this approach may introduce complexity and confusion for users, so it’s not a priority at this time.

A brief GIF video demonstrates the basic interaction with the bot via Skype.

Download EaseHome

All Tutorial Downloads

Here are the source code projects built for EaseHome, click to download it directly.

- Microsoft Bot Connector Proxy

- Luis Project File

- Local Chatbot Client

- CC3200 Project

- Speech-To-Bot Sample